Kill-Grief by Caroline Rance

Research, real life, and remembering the forgotten

I’m thrilled that people have been reading this blog and asking questions (even some people I’ve never even met), so this post will focus on the subject that has turned up most often in the comments – research.

Sometimes when I tell people that I write historical fiction, they say it must be difficult because of ‘all that research.’ But no, that’s not the difficult part at all.

I write historical fiction because I love doing research, rather than feeling that research is a necessary evil towards writing historical fiction. I love the wild goose chases and the tenuous links that just might bring everything together. I love unearthing an engraving of a building; a map or a portrait; a letter in the copperplate of a real-life character whose fictional counterpart has, in my imagination, just flung his pen across the table.

Kill-Grief arose from research I wanted to do anyway. This was in 1998 for an undergraduate dissertation, and I’m aware how incredibly unimpressive that sounds. Going to university is nothing unusual these days and there’s a popular image of students blindly churning out whatever the lecturers tell them, wanting a degree for no other reason than to get the high-flying job that graduates (other than me) can supposedly walk into. I don’t buy that Daily Mail version of students. It might be considered a disgrace that final-year undergraduates only get four hours a week of formal tuition, but for saddos like me, it’s great - it frees us up to do 60 hours a week of research!

In the comments the other day, Rachel asked how I got interested in Chester Infirmary. I decided on 18th-century hospital care as a subject for my dissertation after my first idea – the medical dangers of the pursuit of beauty – met with a lack of enthusiasm from the tutor. As the essay was never going to be an opus to rival the works of Roy Porter, I thought it best to concentrate on one hospital. I chose Chester mainly because I already knew the city, and because I could call in to Wirral to see my Grandma and get free food.

The idea for Kill-Grief took a long time to develop. I liked the idea of writing something based on what I’d studied, but my first attempt was very different and, although the setting and character names were similar, the plot (such as it was) was nothing like the book that’s going to be published. So although I sometimes think I’ve been writing Kill-Grief for 10 years, I haven’t really – the first go wasn’t the same book and it thankfully fizzled out unfinished. I started on other stories, but they were all too rubbish even to qualify as the requisite manuscripts under the bed, so I see Kill-Grief as my first-written novel as well as my first-published.

Rosy commented on the gruesomeness of the research - and the mud! Those two things, would you believe, are linked, and this has given me an idea for something to write about next time.

Michael asked whether any of the characters or plot threads were based on real-life people or events. Not really, is the answer. A lot of historical fiction does centre on real-life characters, usually those well known to posterity – the name ‘Boleyn’ is pretty much a free ticket to a starring role in a novel (and perhaps to being on the front cover, according to Sarah’s theory!) I love to read fiction about these fascinating people, but when writing I am more interested in the obscure and voiceless – those who have slipped through history’s net without ever recording their thoughts.

Many of the characters in Kill-Grief are based on staff who worked at Chester Infirmary in the 1750s, but the link is usually no more than a name. Nearly everything about their personalities and what happens to them is completely made up.

The only thing in Chester Infirmary’s records that relates directly to the plot is a sentence from a Board meeting in April 1756, when the Governors noted that the porter had been dismissed for frequent drunkenness. They sent him on his way with the wages he was owed plus an extra ten shillings, and then that’s it – he fades from history forever. This tiny snapshot from the life of an unknown person inspired the alcohol theme in Kill-Grief, and made me consider how many people have existed without leaving behind even so much as that sentence. Kill-Grief is not their real story, but I hope it acknowledges that they did have a story, however much it’s been forgotten.

July 17th, 2008 at 1:14 pm

Caroline

I will be intrigued to hear how the gruesomeness of the research and the mud are linked! Was Chester very muddy during this period?

July 17th, 2008 at 5:25 pm

Hi Rachel

The main streets were paved, but there was a coating of filth on top - manure from horses and cattle, rubbish from the houses, mud brought in by coaches from the bad roads outside the city - which when mixed with rain turned into a rather insalubrious slush. There was an open drainage channel down the middle of each street to carry away sewage etc, but these easily got blocked. Householders were responsible for maintaining the paving and cleaning the area in front of their own property, but not everyone was very thorough about it. Having said that, Chester was considered healthier than other cities, because the Rows and City Walls allowed people to keep out of the dirt.

July 17th, 2008 at 10:26 pm

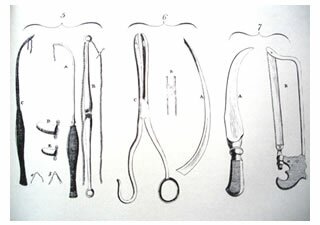

Hi Caroline - I’m a little worried: you told us that the next picture up would be your dog so if this is your dog … its got a problem.

Did you unearth much on surgery in the 1750s for your research and do those instruments appear in your novel?

July 18th, 2008 at 10:28 am

Hi Andrew,

I decided it might be a bit whimsical to put up a pic of the mutt, but for anyone interested, she’s on this page along with my horses: http://www.carolinerance.co.uk/ponies.htm

Anyway, yes I did come across some very interesting sources about 18th-century surgery, and there are a few surgical procedures in the novel. Although I did lots of general reading about medical/surgical history, for these scenes I made a point of only referring to sources written at the time, so as to avoid the risk of later knowledge creeping in. Although instruments like the ones above do feature in the book, I don’t go into great detail describing them, because to the characters they are nothing unusual.