I asked the herbalist at this stall at a market in southern Africa what he could recommend me. He looked me up and down – with what I realised later was pity – pointed to a jar, and said, ‘This one.’

‘And how will it help me?’

Without hesitation he said, ‘It’ll make you become a strong man.’

The rest is history.

Writing and practicing medicine can look horribly incompatible. By that I don’t mean that it should never be done simultaneously, like cleaning your teeth and kissing, or that if you practice one, you should not attempt the other – there are many well-known novelists, ancient and modern, who’ve combined both. I mean that they require two polar opposite forms of brain activity. Medical work requires a flitting, rapid, decision-making type of thinking. It requires moving, alas too quickly, from one patient to another on the wards or in a surgery, stethoscope on a chest one moment, phone to the ear the next, fingers on the computer keyboard the next, mouth to the Dictaphone the next, then your pen scrawling on a form, then a hand in a glove…, then a needle in a vein (apologies – I hadn’t intended to make you feel queasy). Writing, in contrast, requires stillness, a space for drifting thought, what Doris Lessing calls ‘that empty space, which should surround you when you write … into that space, which is like a form of listening, of attention, will come the words …’

However, as in other areas of life, one endeavour can inform the other. There’s the useful insider’s knowledge that any writer has from their other work – yes, there’s some medicine in The Ghosts of Eden although it’s mainly confined to an emergency operation where the surgeon has got more on his mind than the patient – but an awareness of the importance of storytelling can also inform the practice of medicine.

When we fall ill or life treats us rough, certain events occur, we take some sort of action, we feel emotion. But when we tell others, and ourselves, about it at a later time, we construct a story which is selective – we choose which events, which actions, and which feelings, will go into the story. We create a narrative. Psychologists and academics in medicine have long been interested in this – they talk about narrative based medicine. There are people who write dissertations on it. Narrative, they say, provides meaning, context and perspective on our situation. Sustaining fictions (the word fiction being used in the sense of a story rather then a falsehood) underlie the way we present our symptoms or problem to the doctor or therapist. Knowing this, the doctor can see their task as making a contribution to the patient’s narrative plot; a contribution that we, as patients, will find useful. The doctor can become a co-author, an assistant autobiographer, helping us to re-invent our story, to reframe it. The doctor can also tease out the wider story; find the fuller narrative. We all know that stories can accommodate suffering and difficulties, giving them meaning, but if the story is allowed to become fixed then we, as patients, can become trapped within the narrative. A rigid story can close off choices relating to how we react, what we do about our situation. However, with help to reformulate the narrative, we may emerge in the story as a principal character who has found some peace of mind, or is vindicated, or has renewed determination, or perhaps is just heroically coping or, not infrequently, battling through to a cure.

Narrative may have importance beyond our immediate situation. Many have suggested that narrative is fundamental to who we are. Oliver Sacks writes, ‘We have each of us a life-story, an inner narrative – whose continuity, whose sense, is our lives. It might be said that each of us constructs, and lives, a ‘narrative’, and that this narrative is us, our identity.’ Personhood and narrative are inseparable. Jeanette Winterton wrote recently ‘it’s better to read ourselves as fictional narratives, instead of a bloated CV of chronological events.’ A musician (the subject of a BBC documentary) had a brain haemorrhage that deprived him of the ability to remember anything except the previous few seconds. He’s lived a constant battle to discover who he is. He’s a man with no internal narrative.

This is all getting away from The Ghosts of Eden (for masterful digressions see Michael Bollen’s blog below); or perhaps not: schoolboy Michael’s, and herd boy Zachye’s internal childhood narratives, as far as they are concerned, end up destroyed. To achieve redemption/peace of mind they have to re-write their narrative, attempt to reformulate their story to encompass the before and the after.

Hope that doesn’t sound too abstruse – fortunately stories can also be read as entertaining and distracting yarns, although never when you’re a doctor in the consulting room.

Tomorrow: blood and milk for breakfast.

This is the last day of my blog-week and I would like to thank all those who are still doggedly reading it and those that have commented. And very special thanks to those who, at my personal pleading, have restrained themselves from commenting – you know who you are, only one day left to control yourselves, you can do it.

This is the last day of my blog-week and I would like to thank all those who are still doggedly reading it and those that have commented. And very special thanks to those who, at my personal pleading, have restrained themselves from commenting – you know who you are, only one day left to control yourselves, you can do it.

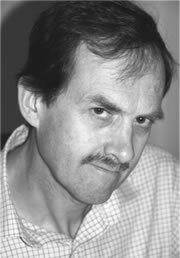

Hello, I’m Andrew Sharp, and am next to walk the plank into the Picnic blogosphere. My first novel, The Ghosts of Eden, will be out with Picnic’s 2009 list.

Hello, I’m Andrew Sharp, and am next to walk the plank into the Picnic blogosphere. My first novel, The Ghosts of Eden, will be out with Picnic’s 2009 list.