Crooked Mile by Ben Beazley

Wednesday, July 30th, 2008 Can I just finish off what I was talking about yesterday in relation to pulling ideas for fiction out of what on the face of it is basically a simple transcription job.

Can I just finish off what I was talking about yesterday in relation to pulling ideas for fiction out of what on the face of it is basically a simple transcription job.

Let me first explain what I am doing at the Record office. From the late 1830’s up until well into the next century, local authorities were required to set up local Boards of Guardians to administer the Poor Laws. A part of this task involved the setting up of Workhouses for the admission of the more extreme examples of those suffering various forms of deprivation. Sorry to teach those of you who are clued in to suck eggs … I will move on quickly to the bits that are not such common knowledge.

Whenever a family or an individual was admitted to the Workhouse, the fact was entered into a ledger along with details of age; occupation; religion; and the reason for their admission. All right, pretty basic book keeping, until that is you have been doing it for a while and start to notice anomalies and wonder about certain things.

After a month or so of burning daylight on Thursday mornings trying to decipher the different handwritings in the legers, the first thing to point out becomes glaringly apparent. Everyone in those days was not possessed of the ability to produce the beautiful calligraphic script of popular belief ! Some of the hands are of quite poor quality and leads to the inevitable conclusion that, as in the modern day prison system, there were those of the inmates who were regarded as ‘trustees’ and helped out in the reception process by entering up the ledger.

Having written down the same names time after time on the admission and discharge balances, after a while a second fact emerges. The basic stated premis of the Workhouse was that staying there should be infinitely less palatable than being in prison. However on a regular basis, and we are not talking about casual vagrants seeking a night’s board, whole families were coming into the house, staying for a few days and then being discharged, sometimes to be re-admitted within hours. So was it then as now – there are those who know how to beat the system ? It seems so.

Also despite the fact that numbers were understandably higher in the winter than in the summer, suddenly around 1884 there is a dramatic fall in the occupancy of the Leicester Union house, from around a thousand to just over six hundred. Why? I suspect that the Guardians ran a cost cutting exercise, (possibly on a national basis), which allowed them to change the ground rules on admission, and tip out a large number who were considered excess to requirements.

Then there is the social dynamic running through everything. Pregnant women, abandoned by lovers or husbands were admitted apparently at the onset of labour and discharged within days of giving birth. So a pretty fundamental form of maternity care becomes apparent. However, quite often the child – who after it’s birth was admitted to the house and recorded simply as a ‘male or female child’ before on the opposite page being discharged with the mother – was not born in the same parish as the workhouse. So the conclusion must be that the women were shipped out to other premises – a birthing house some distance away – for the confinement. This brings up another quaint concept as stated in the house rules that, ‘where a child is born to a woman out of wedlock, no liability for the child shall fall upon the father’. Try that one on the Child Support Agency.

During the summer months numerous children were admitted having been abandoned by their parents. It becomes apparent that this is in fact an approved process initiated by the poor themselves, to establish a system of foster care for their offspring whilst they go into the country fruit picking and harvesting. On a different tack, individual children are often taken out ‘to the service of Mr or Mrs so-and-so, at such-and-such an address’ . When curiosity gets the better of you and you look up the address in Wright’s or Kelly’s directories, you find that it is a shop or manufacturing premises.

So it is easy to see that, with more questions being posed than answered, for someone whose mind is occupied looking for a decent plot, here are a whole series of snapshots that can be factored into a storyline somewhere.

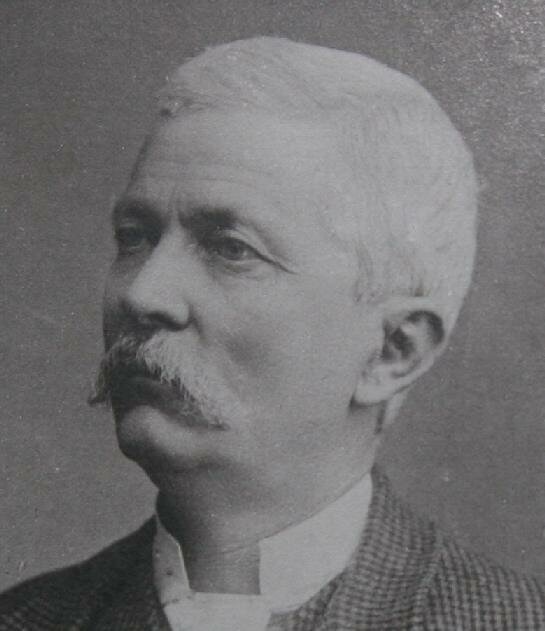

One thing about characters. The golden rule for me is as far as possible write about things, places, and people you have encountered, or know about. In putting together the plot for Crooked Mile I really had very little difficulty in finding the players. I don’t think I mentioned previously that I spent most of my working life as a serving police officer. That in itself when putting together a murder-mystery is I have to say a pretty big advantage – especially as my early days were in the 1960s before the advent of modern technology – radios, computers, and street lights, which sort of gives me things in common with some of the characters. I certainly used people who I knew and worked with over the years as the basis for many of those in the book – Detective Inspector Joseph Langley definitely existed, as did the editor of the Kelsford Gazette, Charles Kerrigan-Kemp. Others, even down to minor characters, were people who over the years I have met – it is so much easier to bring a figure to life if he or she is based in the writer’s mind on fact.

www.benbeazley.com email:

I feel a bit like Scott of the Antarctic, sitting in his tent in 1912 with an icy blizzard howling around outside, scribbling away with a stub of pencil, wondering what to say next …

I feel a bit like Scott of the Antarctic, sitting in his tent in 1912 with an icy blizzard howling around outside, scribbling away with a stub of pencil, wondering what to say next … Having taken over the baton from Andrew and left him taking his well earned sundowner, I find myself at something of a loss to know where to make a start today.

Having taken over the baton from Andrew and left him taking his well earned sundowner, I find myself at something of a loss to know where to make a start today.  This is the last day of my blog-week and I would like to thank all those who are still doggedly reading it and those that have commented. And very special thanks to those who, at my personal pleading, have restrained themselves from commenting – you know who you are, only one day left to control yourselves, you can do it.

This is the last day of my blog-week and I would like to thank all those who are still doggedly reading it and those that have commented. And very special thanks to those who, at my personal pleading, have restrained themselves from commenting – you know who you are, only one day left to control yourselves, you can do it.

Hello, I’m Andrew Sharp, and am next to walk the plank into the Picnic blogosphere. My first novel, The Ghosts of Eden, will be out with Picnic’s 2009 list.

Hello, I’m Andrew Sharp, and am next to walk the plank into the Picnic blogosphere. My first novel, The Ghosts of Eden, will be out with Picnic’s 2009 list. When I was 14, my English teacher asked everyone in the class to write a novel.

When I was 14, my English teacher asked everyone in the class to write a novel.