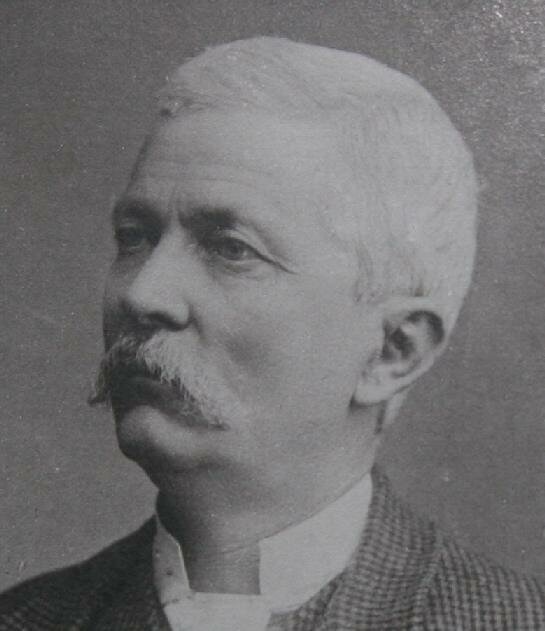

This portrait is not of myself (although it’s an improvement). It’s Henry Morton Stanley and the reason it’s there is that herd boy Stanley, one of the principal characters in The Ghosts of Eden, was named by his father after the controversial explorer, for reasons that are revealed in the book.

Yesterday I found myself writing what might have looked like a rather bloated back-cover blurb for The Ghosts of Eden … which got me thinking about back-covers. I’m as suspicious as anyone else of those book-jacket pitches and recommendations – ‘if your life isn’t changed for ever by this book, you’re a corpse,’ sounds like a threat – and yet, when browsing the shelves, short of speed reading (and here one is likely to end up with the same superficial impression that Woody Allen had when he speed-read War and Peace: ‘it involves Russia’), there’s not much choice but to turn the book over and see what lavish adjectives the publisher has coughed up. Don’t misunderstand me: I’ll strangle myself with my stethoscope if the blurb on the back of my own novel isn’t purple with hyperbole – Picnic please note! – although Chris Power, writing at blogs.guardian.co.uk/books/2008/05/how_to_judge_a_book_by_its_cov.html

says that for him the most useful back-cover text is a quote from the manuscript itself. To paraphrase him: it’s not the setting, it’s not who it’s about, it’s not even the plot, it’s about being stimulated by the writing.

Many years ago there was less back-cover lather: a simple statement on the genre, what to expect in general, and perhaps a straightforward opinion on who would find this novel of interest. I’m not suggesting that opinion was quite as forthright as Dorothy Parkers’ ‘This is not a book that should be cast aside lightly, it should be thrown with great force’, but there was a little more restraint and honesty, which allowed the potential reader to form a less suspicious opinion on the contents. For example, there’s a book, long out of print, titled In Search of Paradise aimed at retirees looking for an Eden. The back cover reads: ‘Much of the book is written in his usual flippant way, but …’

That brings me, by a curiously circuitous route, to one of the triggers for the setting, that Aigen asked about yesterday, for The Ghosts of Eden. The place, in all the world, that the author of In Search of Paradise judged (and I can detect no flippancy here) most akin to his idea of paradise was an island on a small lake in southern Uganda. Carried over the water in a dug-out canoe, the island appeared ‘through a light opalescent haze. The house was there, beautifully shabby, as though it was a natural part of the island. The green lawns, cropped and velvety, swept down to the water’s edge. It was like seeing a ghost, so faithfully did it tally with my dream picture.’ The island happened to belong to my grandparents (who started a leprosy treatment centre on another island – but that’s a different story). I remember the surging strokes of the oarsmen and the rhythmic splash and suck of the paddles when I visited the island as a small child.

So I too was entranced, but not just by my grandparents’ island but by the dramatic landscape of volcanoes, lakes and mountains. The eastern arm of the Great Rift Valley is well known – think Out of Africa, White Mischief – but the western limb that divides the savannahs of East Africa from the great forests of the Congo basin is less frequented, but even more spectacular, and was the scene for the search for the source of the Nile by those iron-jawed Victorian explorers.

I always knew I wanted to set a novel there but a big landscape requires a big story with strong themes so The Ghosts of Eden has been a long time in gestation while I’ve mused on the characters and their lives. Most stories worth reading, and worth writing, attempt to open new windows on universal human experiences such as loss, the struggle to survive it, the courage necessary to overcome, or the sacrifice that might be necessary to find love. I can only hope that mine is not too many thousands of miles away from that type of story. Similar themes are found in stories from every culture throughout history. They also find their way into the story of our own lives. Which, in this meandering blog, leads into the stories we present to doctors. Something about that tomorrow.

Hi, Andrew,

Thank you for the very informative reply to my questions. I’m enjoying your blog very much and this second entry leaves me even more anxious to read the book. I particularly like the quotes that you insert here and there. You evidently know this landscape, its history and people very well. Now you’re giving us clues to your medical background. Do I ask more questions or wait for tomorrow’s blog?

Aigen.

At the risk of sycophancy (as an arch-neologizer) I have to blog in support of my friend and say that this entry is reminiscent of another most excellent of stories “Hirundininae et Amazonia” – indeed to quote another Blogger – “Sharp (Side: ) was Arthur Ransome” (http://ellissharp.blogspot.com/2005/03/was-arthur-ransome-working-for-mi6.html). And to continue the misquotation with a Dickensian allusion: Andrew/Pip we have Great E… of you – and I might add (lingua en bucca) that: are we sure no plaguarism has occurred here, noting that according to Wikipedia: “The action of the story takes place … when the protagonist is about seven years old… is written in a semi-autobiographical style, and is the story of the orphan Pip, writing his life from his early days of childhood until adulthood.

Enough I hear you cry!

Hi Aigen, I hope you enjoy the remaining blogs. Tomorrow’s touches a little on medicine. I’m skipping around with these blog entries to find something of interest to a wide range of people. I’ve lived in East Africa (and Zimbabwe – where I’m basing my next book) so enjoy writing about it. There’s quite a lot of post-colonial Indian fiction but not so much set in Africa.

Hi Pete, thanks for your entertaining comments. I’ve kept away from auto-biography – even semi – in the novel although I think that Milan Kundera said something like: The characters in my novels are my own unrealised possibilities. That, I suspect, holds true for many writers.

Andrew, The note about your dream island put me in mind of Rose Macaulay’s'Orphan Island’ or even Mary Rose(J.M Barrie, I think?) and the trauma of her double disappearance. The dream can degenerate into a nightmare all too easily. I think you really are opening new windows. Good luck with the book Mel

I found your site on technorati and read a few of your other posts. Keep up the good work. I just added your RSS feed to my Google News Reader. Looking forward to reading more from you down the road!